SCAnDi: Single-cell and single molecule analysis for DNA identification.

The end of the “DNA Smoothie?”

Why prosecutors and defense attorneys need to watch this novel single-cell DNA technology.

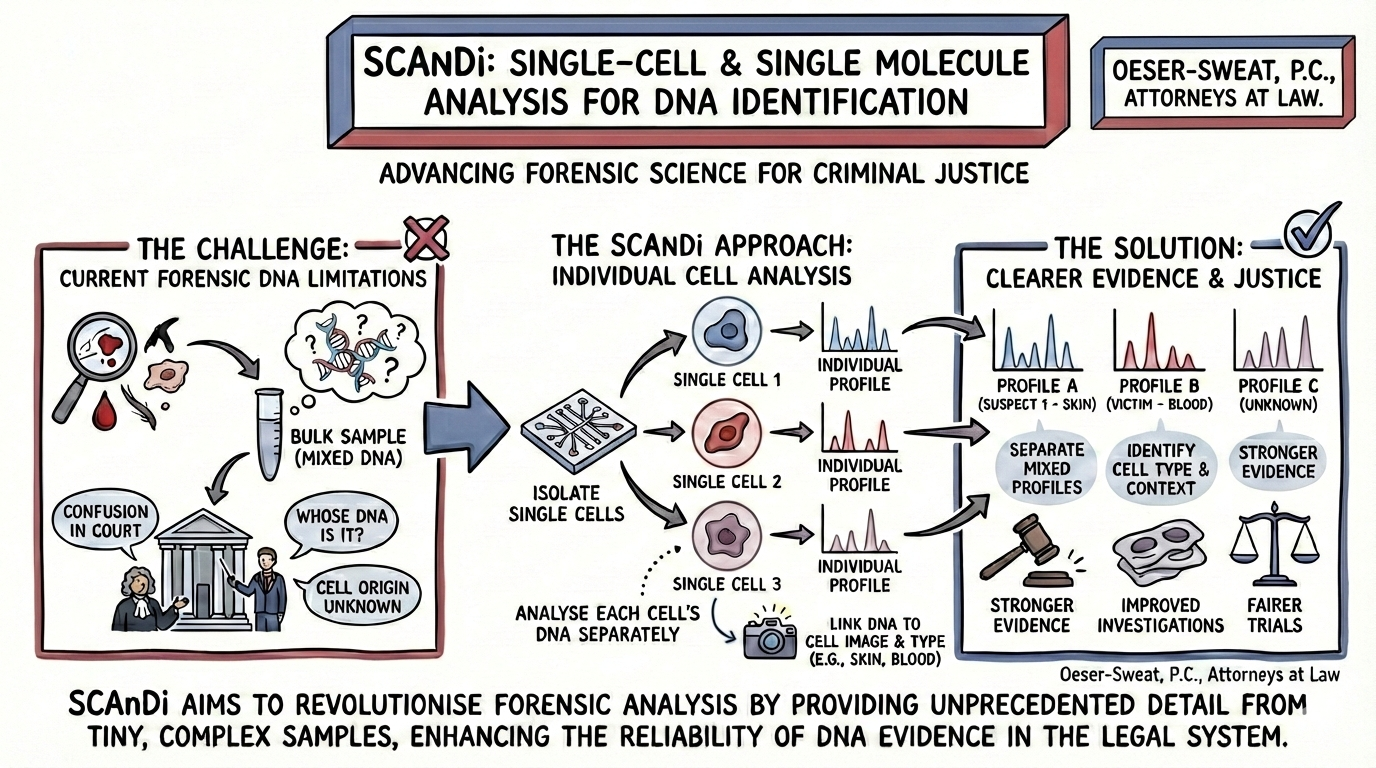

DNA evidence has long been considered the “gold standard” of forensic science. But it has a major weakness: mixtures. When multiple people touch the same object, their DNA gets blended together, often leading to inconclusive results. A new technology currently in development, SCAnDi (Single-cell and Single Molecule Analysis for DNA Identification), promises to solve this problem by analyzing individual cells before they are mixed.

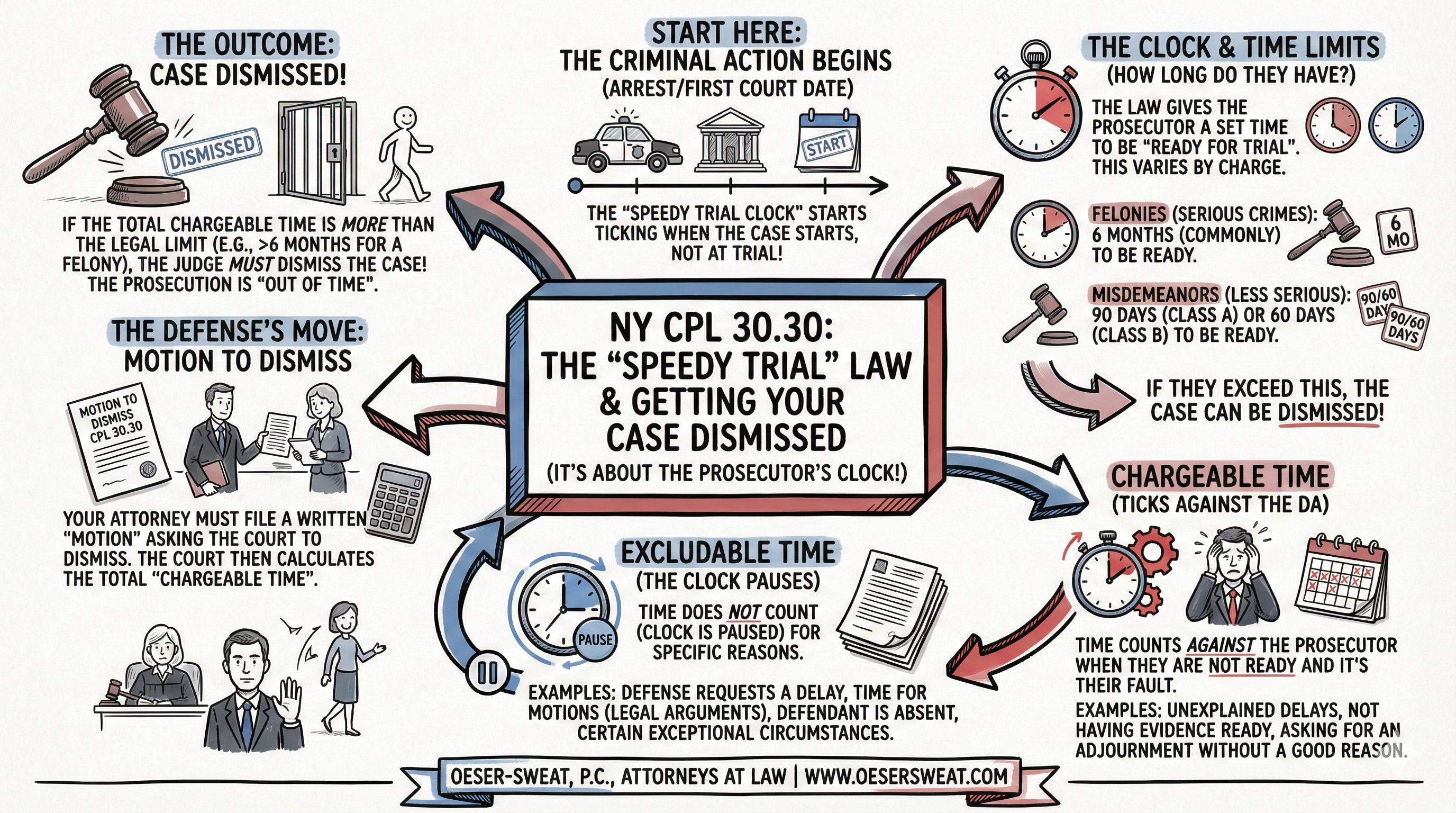

View Text Description of Infographic

The Old Way (“DNA Smoothie”): Current methods take a bulk sample (e.g., a swab from a doorknob) and mash all the DNA together. If three people touched it, you get a mixed profile that is hard to interpret.

The SCAnDi Way: This new tech uses a flow cytometer or similar device to physically separate individual cells before DNA extraction. Each cell is analyzed separately.

The Result: Instead of a mixture, you get distinct profiles: Profile A (Suspect), Profile B (Victim), and Profile C (Unknown), with no ambiguity.

1. The Problem: The “DNA Smoothie”

Current forensic methods rely on “bulk samples.” Imagine a crime scene doorknob touched by the victim, the suspect, and a police officer. When the lab processes the swab, they extract DNA from all three people simultaneously. To a scientist, this looks like a “DNA Smoothie”—a jumbled mix of genetic code.

Analysts then have to use statistical software (like STRmix) to try to “unmix” the smoothie and guess the probability that a specific person contributed. This often leads to results that are inconclusive or open to fierce debate in court.

2. The Proposed Solution: SCAnDi

SCAnDi stands for Single-cell and Single Molecule Analysis for DNA Identification. Instead of blending the sample, SCAnDi uses advanced technology to pick out individual cells one by one.

- Isolation: The machine isolates a single cell from Person A and a single cell from Person B.

- Analysis: It extracts a clean, “pristine” DNA profile from each specific cell.

- Context: Beyond just identity, SCAnDi can potentially tell us what kind of cell it is. It could prove, for example, that the DNA on a jacket came specifically from saliva (implying spitting or biting) rather than skin cells (implying casual contact).

3. Prosecution vs. Defense: The Upcoming Battle

For prosecutors, SCAnDi is the “Holy Grail.” It moves forensics away from “likelihood ratios” and probabilities toward definitive identifications. It could solve cold cases where samples were previously too mixed to be useful.

Defense attorneys must view this with skepticism. If a machine is sensitive enough to find a single cell, how do we prove that cell wasn’t transferred by a gust of air or “innocent transfer” (secondary touch)? Finding a single skin cell doesn’t prove presence at a crime scene if we shed millions of cells a day.

4. Current Legal Status: Not Court-Ready

It is critical to note that SCAnDi is currently a research project. It looks like a very promising scientific endeavor. However, there are some current caveats. It has not yet been accepted as evidence in United States courts yet. Before a jury ever sees SCAnDi results, the technology must pass the Frye or Daubert legal standards. This requires:

- Peer Review: Publication in scientific journals.

- Testing: Proof of reliability and known error rates.

- General Acceptance: Consensus in the scientific community.

Researchers at institutions like Edge Hill University and the Earlham Institute are currently refining the process and working to advance the science. This work may be groundbreaking. Lawyers on both sides should be watching this space closely.