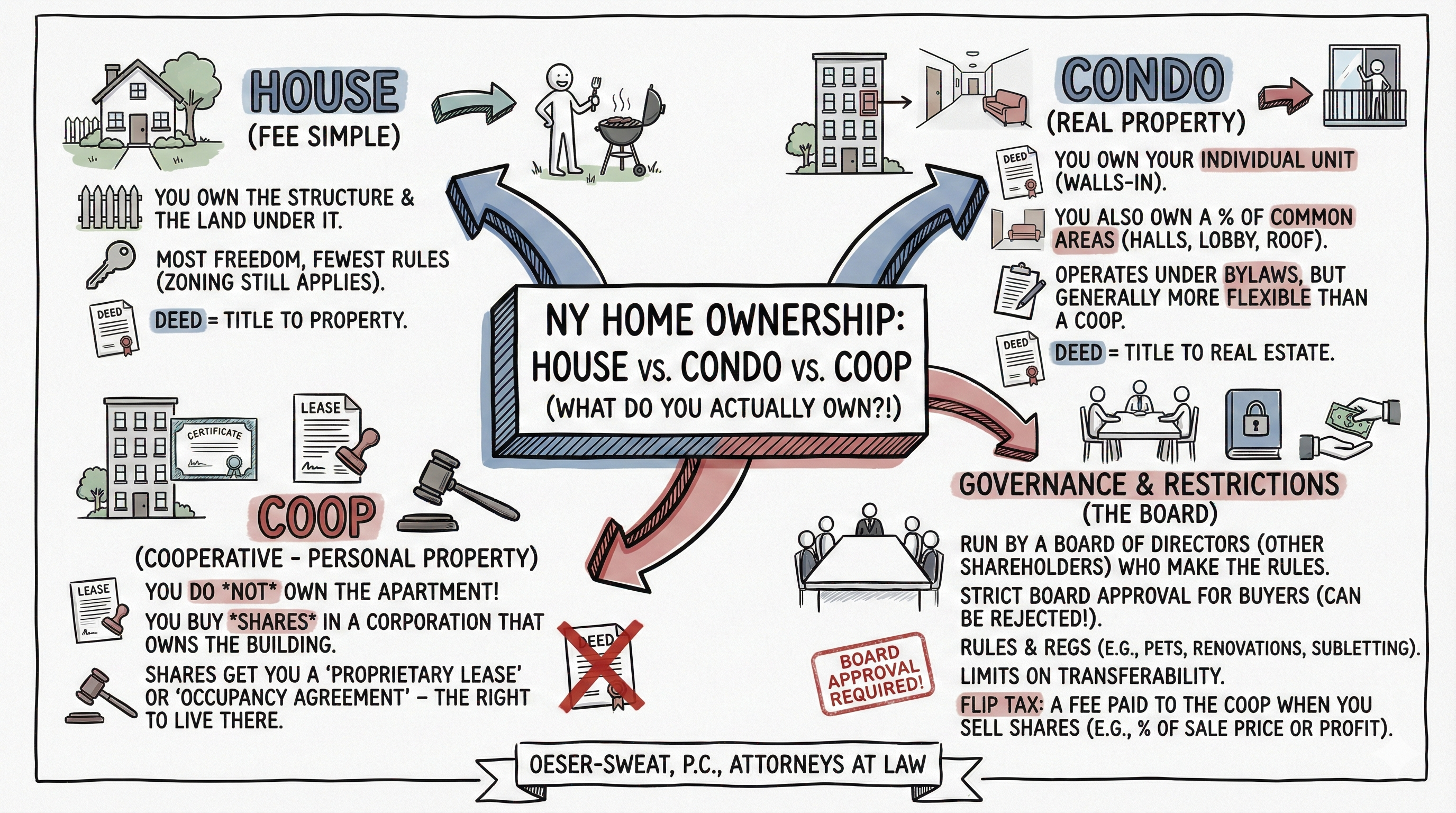

New York City real estate is unique. Not all of the properties you buy here come with a deed. Unlike the rest of the country where you will likely buy a “House” and get a deed, in New York, when looking to buy an apartment, you are often asked to consider buying into a corporation that owns one or more buildings in which you would live as a “tenant” or “shareholder” in one of the building’s apartments. Understanding the legal difference between a Cooperative (Co-op) and a Condominium (Condo) is critical before you sign a contract or hire a lawyer.

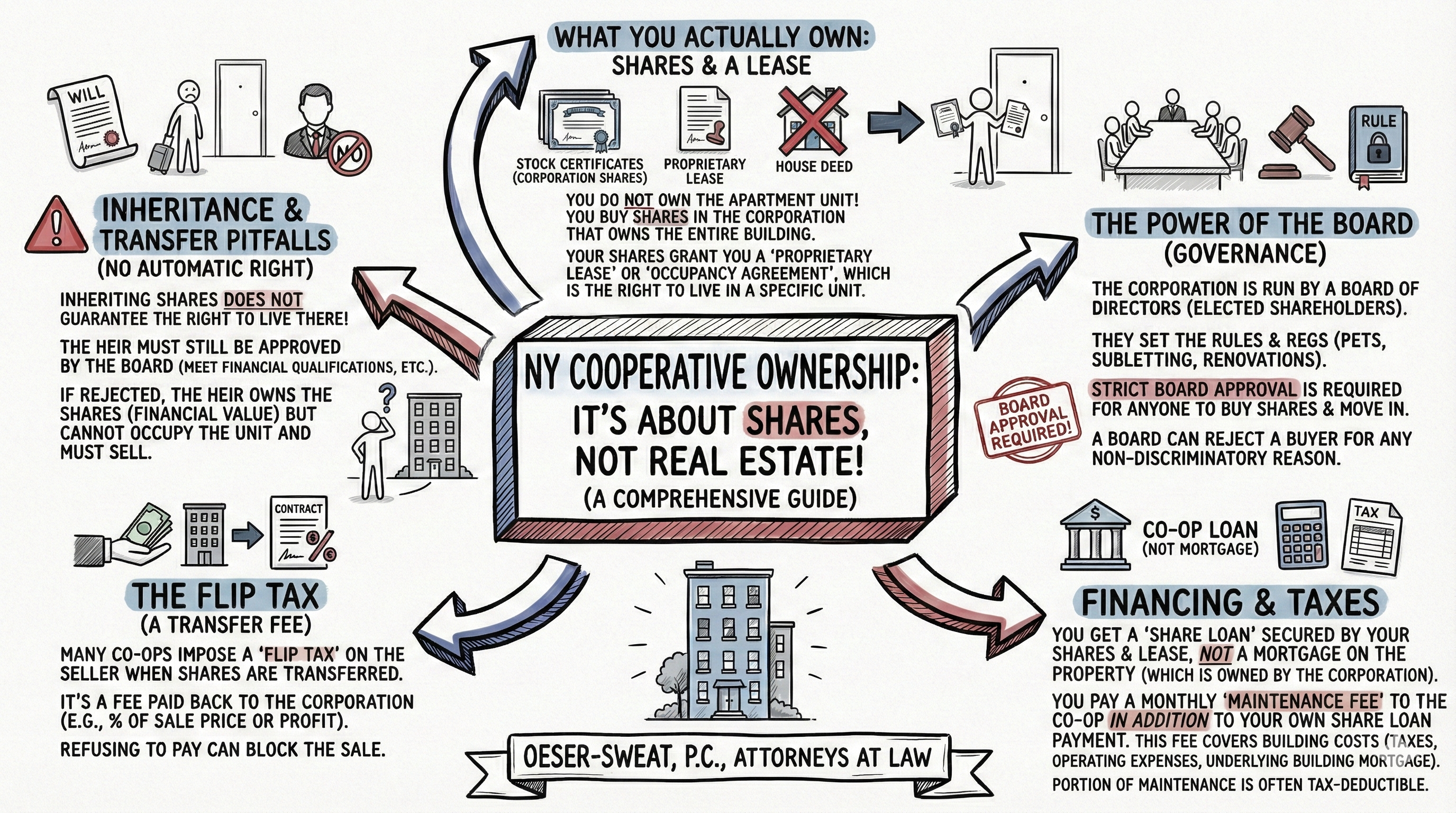

1. Ownership Structure: You Don’t Own the Apartment

When you “buy” a Co-op, you are not buying real estate in a traditional sense. You are buying shares of stock in a corporation that owns the building. Because you own shares, the corporation (usually) grants you a Proprietary Lease which allows you to live in a specific unit.

This is why Co-ops have “Maintenance Fees” instead of Common Charges. Your maintenance pays for the building’s mortgage, the doorman (or super and staff), the heat, AND the property taxes for the whole building. At some Coops, the maintenance even includes electricity, which is a welcome controlled expense for everyone, but especially financially vunerable populations on a fixed income such as the elderly and retirees. Including electricity and heat in the maintenance makes these populations less likely to feel immediate pressure from price increases, as they are more evenly split between a population of shareholders.

2. The Co-op Board: The Gatekeepers

Because you are becoming a business partner with your neighbors, Co-op Boards have immense power. They review your financials, credit, and character references. They require a face-to-face interview. Crucially, a Co-op Board can reject a buyer for any reason (or no reason) as long as it is not discriminatory (based on race, religion, etc.).

Cooperatives have been described by Courts in NY as “a little democratic sub society of necessity”, as a “quasi-government” and even as “a fiefdom”. Board members have a duty to the collective and not individual shareholders. This means if a rule is not good for a single shareholder but benefits the collective, they will likely implement such a rule. If you are the individual shareholder that gets the short end of the stick, notions of duty to the collective will not make the situation any less bitter.

A Board’s decisions will always be compared against something called the Business Judgment Rule. The Board has significant power over the affairs of the Cooperative. These powers come from the State Laws, from the Bylaws, and from the Rules that the Board makes through its authority.

“A governing board may significantly restrict the bundle of rights a property owner normally enjoys. Moreover, as with any authority to govern, the broad powers of a cooperative board hold potential for abuse through arbitrary and malicious decision-making, favoritism, discrimination and the like.” Levandusky v. One Fifth Ave., 75 NY 2d 530 – NY: Court of Appeals 1990

3. Financial Due Diligence: Looking Under the Hood

WARNING: Never buy a co-op without reviewing the building’s Financial Statements.

Since you are buying shares in a business, if the business (the building) goes bankrupt, your shares become worthless. Before signing a contract, your lawyer must check:

- Underlying Mortgage: Does the building have a massive loan coming due?

- Reserve Fund: Does the building have cash saved for emergencies?

- Assessments: Are there major repairs (roof, elevator, Local Law 11 facade work) planned that will cause your monthly bill to jump up?

4. Restrictions and Flip Taxes

Co-op living is restrictive. Before buying, you must know the rules:

- Subletting: Many Co-ops forbid subletting entirely, or limit it to 2 years out of every 5. You generally cannot buy a Co-op as a pure investment property.

- Renovations: You need Board approval to renovate. They can dictate work hours, insurance requirements, and materials.

- Financing Caps: Some buildings only allow you to finance 80% or even 50% of the purchase price.

- Flip Tax: When you sell, the Co-op may charge a fee (transfer or “waiver of option” fee) that goes back to the building’s reserve fund. This can be a flat fee, a percentage of the profit or a percentage of the sale price (sometimes up to 65% in HDFCs, though 2-3% is common. Some coops have flip taxes of 75% within the first two years and 25% of profit thereafter).

- Carpets: Many Co-ops require carpets. As many of these buildings are over a quarter century old, the floors creak and in addition to the normal noises of living, noise can be a serious concern. Many co-ops require carpeting for noise mitigation and heat insulation purposes and as a result, this can be an additional expense to those moving in and can affect your lifestyle.

5. Special Category: HDFC Co-ops

Housing Development Fund Corporation (HDFC) Co-ops are income-restricted affordable housing units. They are significantly cheaper to buy, but come with strict rules:

HDFC Constraints:

- Income Caps: You cannot earn more than a certain amount (based on Area Median Income).

- High Flip Taxes: The building often takes a huge chunk of your profit when you sell to keep the unit affordable.

- Cash Heavy: Financing can be difficult; some require all-cash purchases.

Housing Development Fund Corporation (HDFC) Co-ops are often buildings that were abandoned by landlords or had financial distress in the 1970’s and 1980s and were renovated by HPD to give tenants of the units in the building the opportunity to own their apartments by becoming shareholders with limited equity in a cooperative (HDFC). There are over 1,100 HDFC coops in just New York City. These buildings often get reduced real estate taxes, which significantly reduces costs.

6. Pros and Cons Summary

Advantages: Lower purchase price and closing costs than Condos. Often financially stable with vetted neighbors and a strong sense of community. Often lower carrying costs, which arguably in many cases means that lower sale prices when compared to condos can be offset by the amount of carrying costs over time. If there is a huge problem with the halls or walls, the costs are often borne by the coop as a collective rather than the individual. It costs way less to repair a roof when the bill is split between 50-100 people vs you being the only person paying.

Disadvantages: Invasive Board interviews. Risk of rejection without cause. Strict rules on how you live. Harder to sell or rent out. Boards can change and like the Supreme Court, and major shift in the number of people or changes in philosophy of members can have a significant impact on your day to day life without notice and often without recourse.

Figure 2: The Flow of Co-op Ownership

Figure 2: The Flow of Co-op Ownership