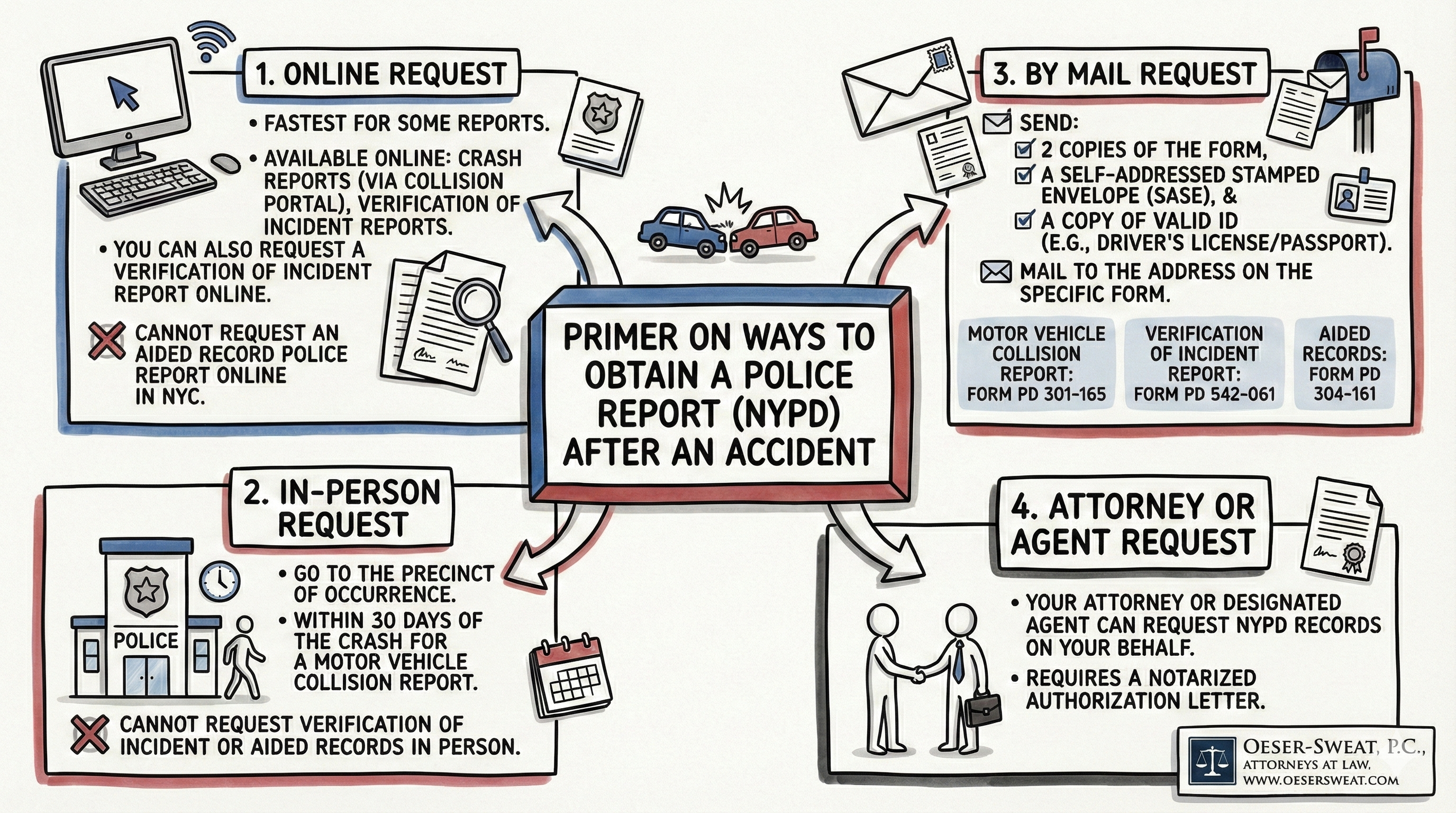

How to Get a Police Accident Report in NYC

A simple guide to retrieving your collision report (MV-104AN) online or by mail.

Getting into a car accident is scary and confusing. Once the dust settles, you need proof of what happened for your insurance company or for a lawsuit. In New York City, this proof is called the Police Collision Report (form MV-104AN). Getting this report used to be easy, but the rules have changed.

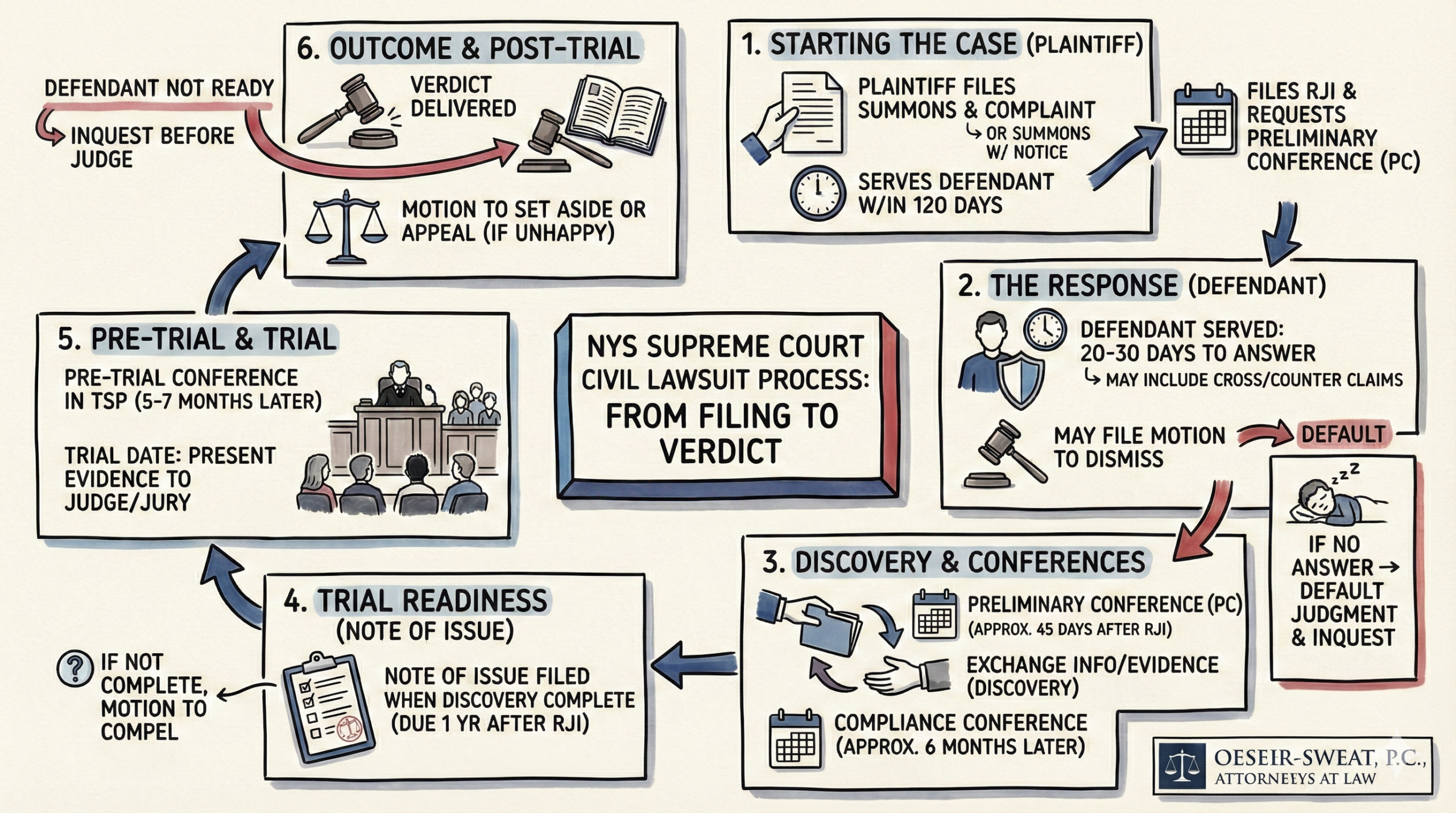

View Text Description of Graphic

1. At the Scene: The police officer writes down the details. You should ask for the “Accident Report Number” or “Complaint Number.”

2. The Wait: It usually takes a few days for the report to be typed up and put into the computer system.

3. Requesting the Report: You can go to the NYPD Collision Report Portal online. You enter the date and your license plate number to find it.

4. Alternative: If you can’t find it online, you have to mail a “Verification of Incident” form to the NYPD Criminal Records Section.

1. What is the MV-104AN?

The MV-104AN is the official form the police fill out when they come to an accident scene. It lists the drivers involved, the insurance information, and a diagram of how the crash happened. This piece of paper is critical. Without it, your insurance company might delay fixing your car or paying your medical bills.

2. Don’t Just Go to the Station (Most of the Time)

To save time and avoid frustration, you should try to get the report online first. If you just show up at the station, they might just hand you a piece of paper telling you to go home and use the computer. You can go to the local precinct where the accident occurred within 30 days and get the report.

3. The Best Way: Go Online

The fastest way to get your report is through the NYPD Collision Report Portal. It is free and available 24/7. Here is how it works:

- It can take up to 7 days after the accident for the report to be available. It takes time for officers to enter the data.

- Go to the Collision Report Website.

- You will need to search using the Incident Date and the License Plate Number of one of the cars involved.

- If found, you can download the PDF right away.

4. The Slower Way: By Mail

If you cannot find the report online, or if the police did not file a full collision report but only made a record of the incident, you have to use the mail. You must fill out a specific form depending on what you need:

- Collision Report Request: Use the form found in the links to request the standard accident report.

- Verification of Incident: Use form PD 542-061 if you just need proof that something happened (like a tree falling on your car) but it wasn’t a two-car crash.

- Aided Record: Use form PD 304-161 if someone was hurt and taken to the hospital by ambulance.

You must include a stamped, self-addressed envelope with your request so they can mail the report back to you.

5. Is There a Fee?

Getting the report from the NYPD website is usually free. However, if you order it through the New York State DMV, there might be a fee. Also, if you are paying for other police records, you might use the CityPay portal. Always check if a fee applies before you send a check.

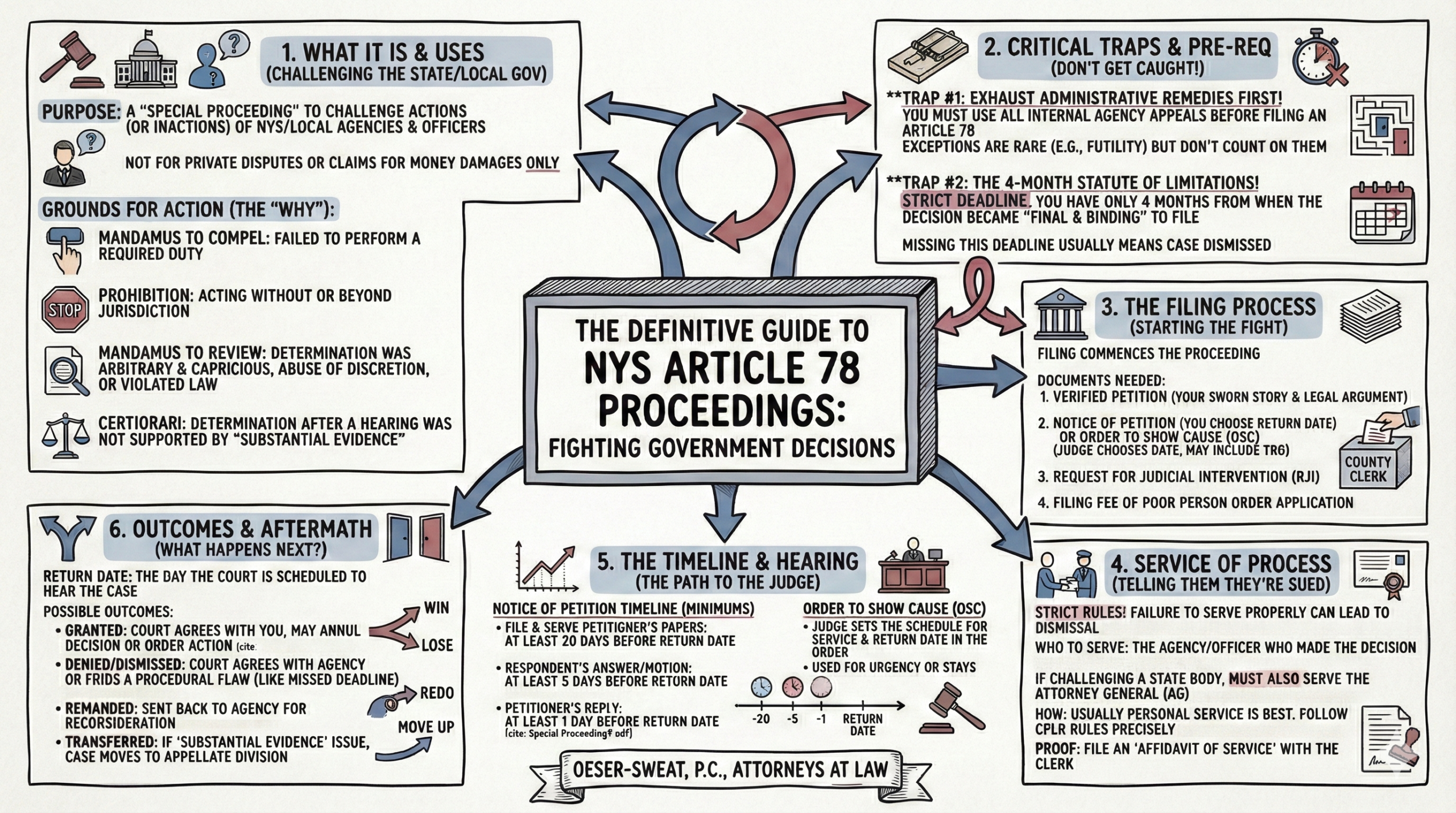

Figure 1: The Lifecycle of an Article 78 Proceeding

Figure 1: The Lifecycle of an Article 78 Proceeding